A Community Potluck: Part 2

The history of Hopkins Grove provides important perspective as it approaches its 175th anniversary

Timing plays a tremendous role in perspective. If you had asked me where Hopkins Grove was earlier this year, I simply would not have known. Also, if you had asked me my favorite quote from legendary science-fiction writer Isaac Asimov that too would have gone unanswered. But that time has passed, as I just finished Asimov’s The God Themselves and recently played a show for the people of Hopkins Grove learning their story. In the final chapter of Asimov’s award-winning book from 1972, a main character says, “there are no happy endings in history, only crisis points that pass” and that line feels like the perfect segue to jump back into the history of Hopkins Grove.

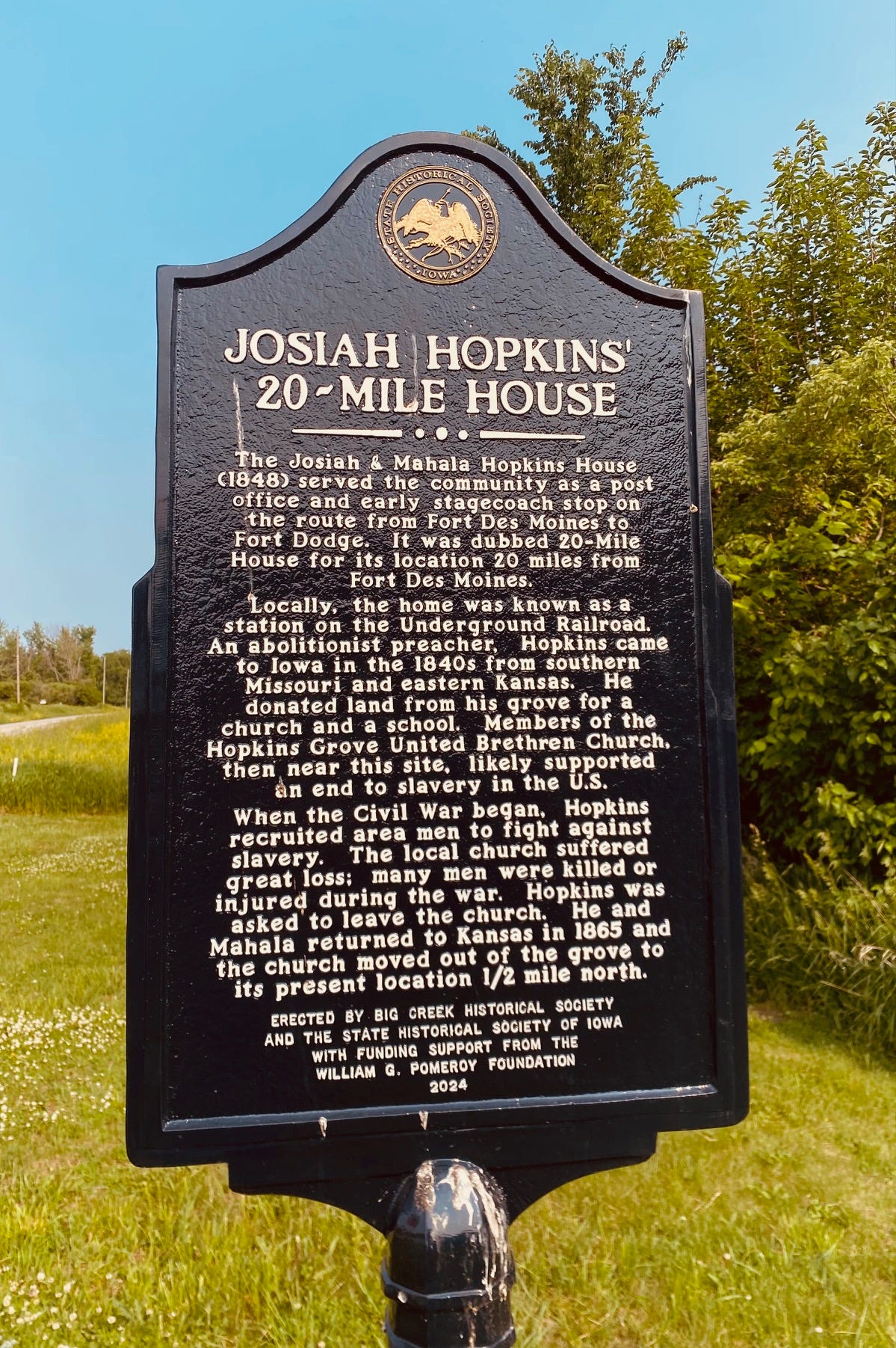

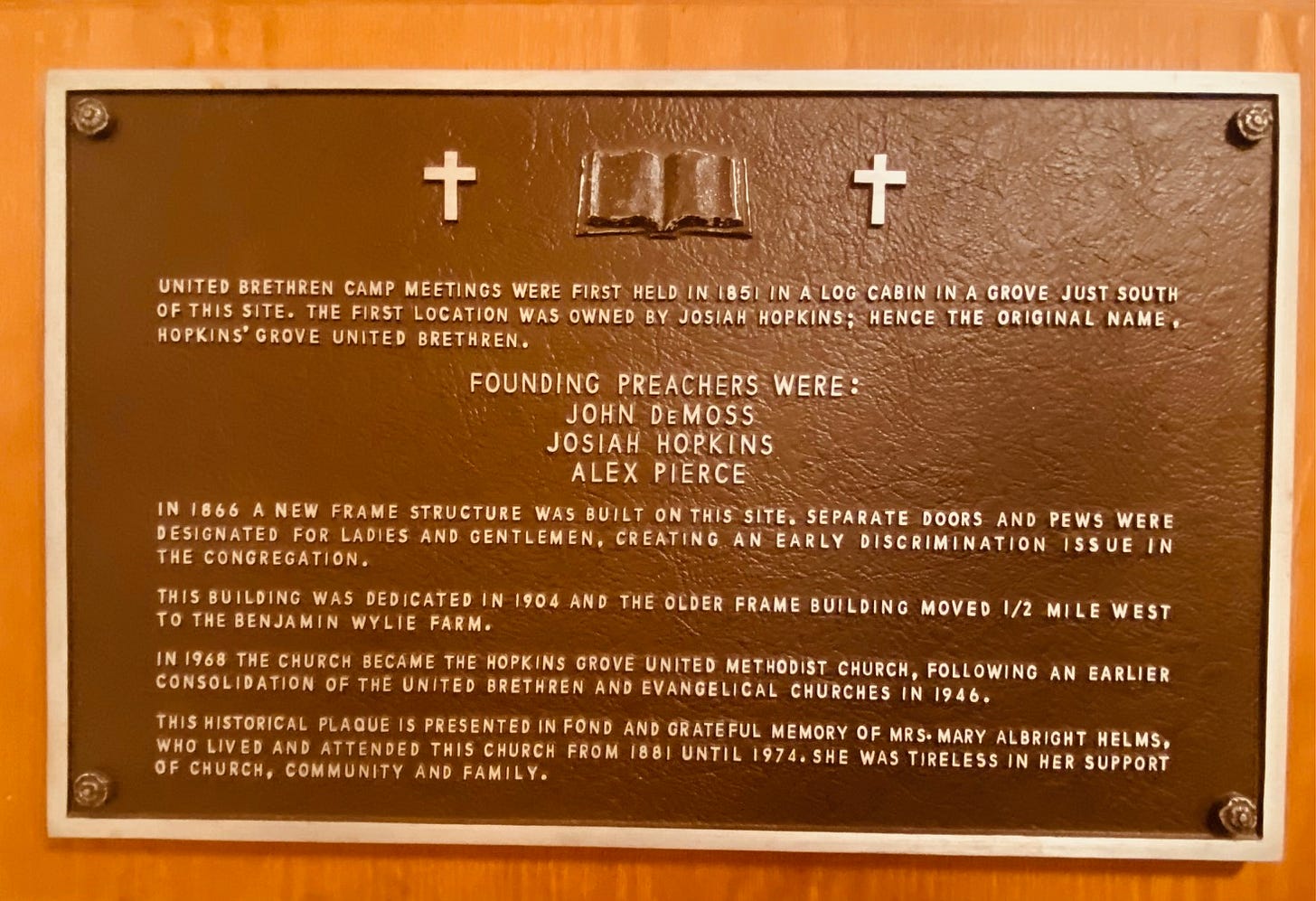

In 1851, the United Brethren Camp first met in a log cabin on the farm of Josiah Hopkins just north of central Iowa’s Big Creek and down in a grove, hence, the Hopkins Grove moniker. Founding preachers for the original Hopkins Grove United Brethren were John DeMoss, Alex Pierce and Josiah Hopkins, a decade before the official start of the American Civil War.

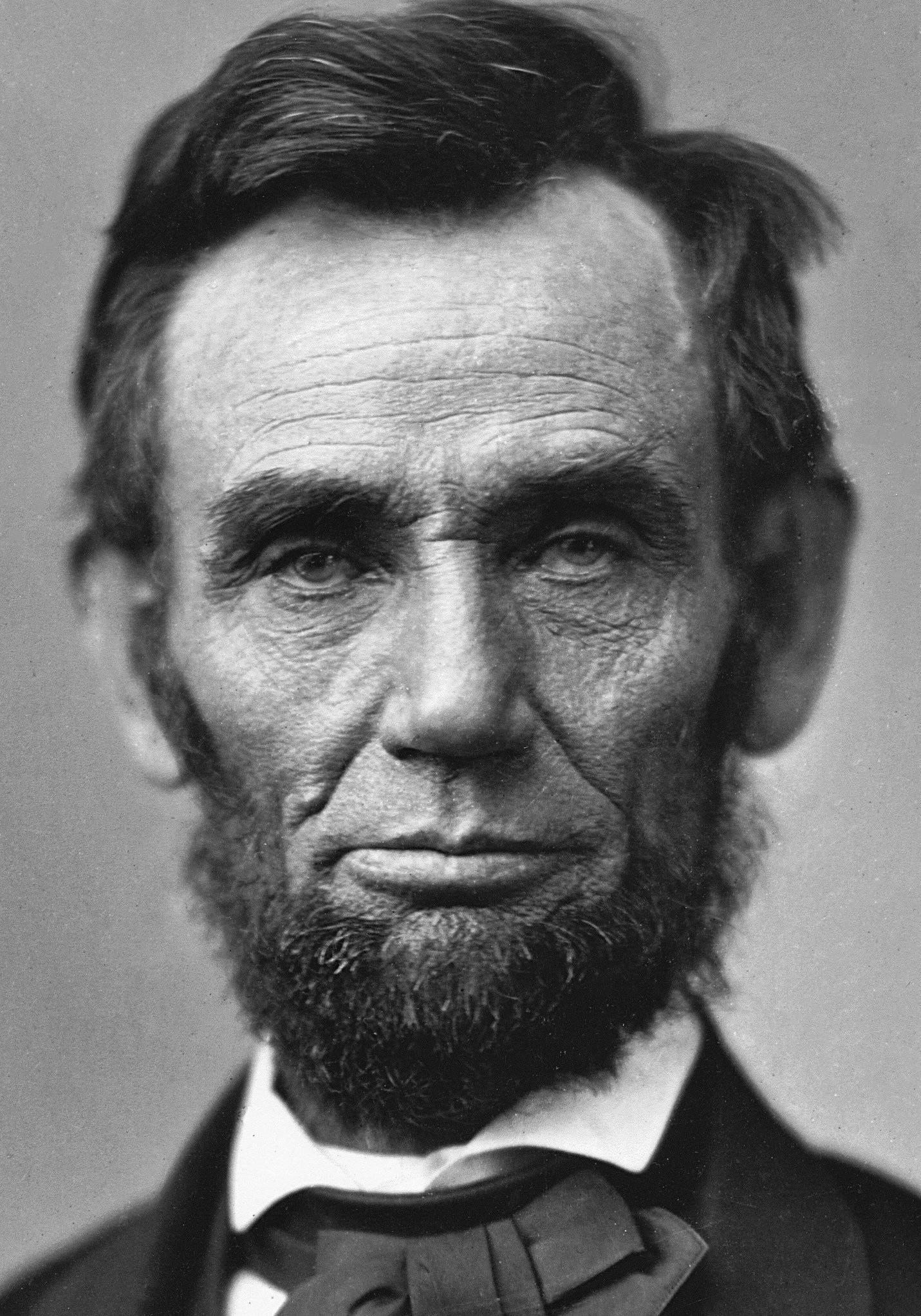

The country was already torn over the issue of slavery in 1851. But, not until the election of Abraham Lincoln (who very much opposed the expansion of slavery) in 1860, would official sparks start to fly with the secession of seven southern states early in 1861 and then all-out war on April 12, 1861, when the South bombed Fort Sumter in South Carolina. A crisis point in America had officially boiled over into a devastating war that would last for more than four years and in result in more than 1 million deaths taking quite some time to pass. Legally, the war did not technically end until a proclamation by President Andrew Johnson on August 20, 1866.

The Hopkins Grove United Methodist Church went through much change and calamity during this time too. The current structure was built in 1866 after the majority of the congregation decided to part ways with its namesake founder. Reverend Josiah Hopkins had been initially revered as “natural leader” and “by all accounts, was highly respected within his congregation and community” according to historian Daniel Higginbottom in his essay Josiah Hopkins: Polk County Abolitionist published in 2012 by the State Historical Society of Iowa.

Many of the details of what officially happened in this small community are forever lost in history, but it is well-known that Josiah Hopkins, an unapologetic Abolitionist, recruited many fellow Hopkins Grove men to join him to fight in the Civil War on behalf of the Union. An estimated group of around 15 from the small community joined him over time and many never made it back home alive.

To better understand the community history, we need to travel back a little farther in time. In the late 1840s, Josiah traveled on a reconnaissance expedition from his homestead in Carthage, Missouri, to the Big Creek area north of Polk City in search of affordable land that was farther away from the slave-owning south. On this original trip to the north, the Hopkins caravan actually passed through my hometown of Fort Scott, KS, and many unsettled territories before feasting their eyes on this beautiful Iowa country.

Upon his return to Missouri, Hopkins’ enthusiasm for a better life in Iowa had the ears of many. According to Higginbottom, “the increasing settlement of pro-slavery landholders in the Ozark Region, the growing competition between free and slave labor and the resulting ideological and economic antagonism, along with a desire to acquire good land cheap in a free state were all sufficient motives for members of fourteen families to migrate from southern Missouri into Polk County in May of 1849.” Land would be purchased by many for a $1.25 an acre.

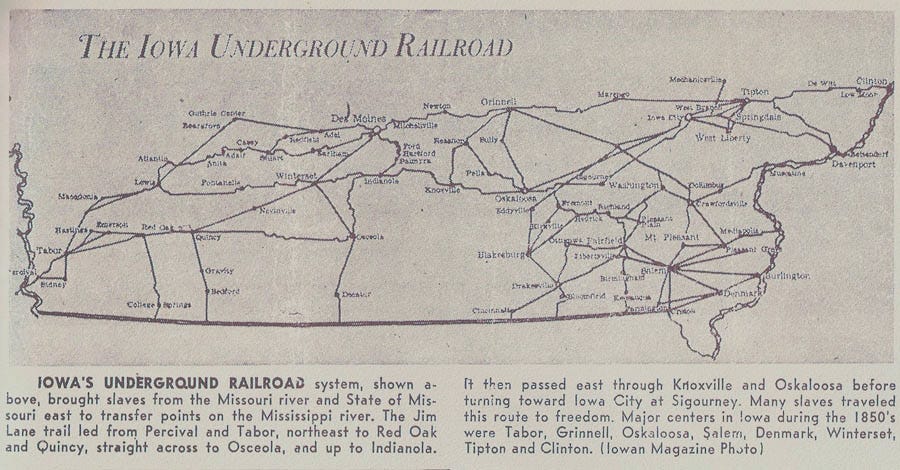

Josiah Hopkins and his wife, Mahala Phebus Hopkins, would officially land in the Madison Township area of Polk County in 1850. The Hopkins clan would eventually begin operating an inn known as the Twenty-Mile House because of its distance from Fort Des Moines. It is now widely known that in addition to Josiah’s agricultural operation, the Twenty-Mile House played a critical role in the Underground Railroad as a conduit for many slaves to freedom through the north, even though it’s often excluded on some maps given the secretive nature of Underground Railroad operations.

The Twenty-Mile House was one of many important support systems for the Underground Railroad in the state of Iowa. According to the Iowa Freedom Trail Project, “Underground Railroad activity within Iowa was quite significant. The state was in a good geographic position to serve as a gateway for the Underground Railroad due to the location of Missouri, a slave state, bordering Iowa to the south, and Illinois, a free state, bordering it to the east. Additionally, the Missouri Compromise of 1820, which provided that no state north of the 36°30′ parallel (besides Missouri) could enter the United States as a slave state, ensured that when Iowa became a state in 1846 that it would enter as a free state. Though not all settlers in Iowa viewed slavery as immoral, many who did came from other free states or were often associated with specific religious communities, such as the Quakers and Congregationalists who openly opposed slavery.”

Josiah Hopkins popularity in central Iowa grew as a powerful speaker and believer in a better humanity. According to fellow preacher, Reverend James Adams, “I considered [him] the best and most useful preacher that the United Brethren ever had in this part of Iowa. He was a good revival preacher. I had a better chance in some respects, to know him than the United Brethren preachers as I belonged to a different church. I was a good deal with him at protracted meetings, political meetings at his house, and other places; and I always found him honest and upright in all his dealings. He was bold to take up and firm to sustain the consecrated and I loved him as a brother. He was an old time abolitionist—an uncompromising Anti-Slavery man.”

Reverend Adams continues, “he was as active perhaps as any other man in trying to raise men and means to put down the rebellion. He not only urged others to enlist but he enlisted himself in the 10th Iowa Regiment Inf., and was in one of the first battles fought by Gen. Grant on the Miss. River [sic]. There he proved himself a brave soldier.”

The camps were hard on the volunteers from Hopkins Grove and saw Josiah himself report back to Polk County in 1862 because of bad health. Furthermore, “the loss of several local boys from Company A to diseases such as measles, typhoid, and ‘chills’” wore hard on the Hopkins Grove community as the war lingered. The Unionist cause gathered more steam with Lincoln’s epic Emancipation Proclamation on January 1, 1863, catalyzing Hopkins to recruit more volunteers and speak out louder in favor of the Union.

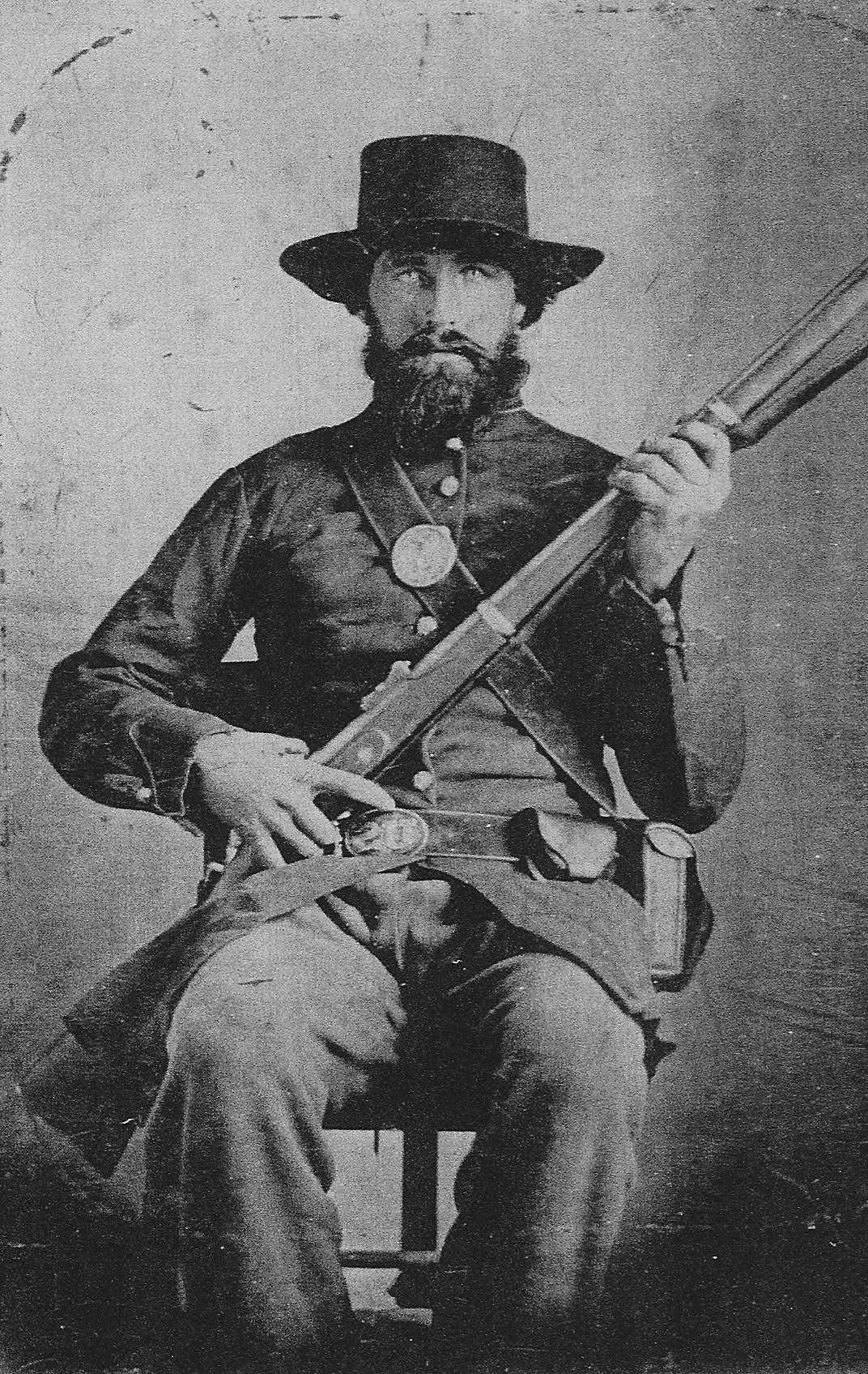

One such recruit was George Washington “Wash” Grigsby who would pass in the war on July 10, 1863, at the age of 35. Through local historical preservation efforts, the George Washington Grigsby stone has been updated and is located behind the current church for visitors to honor. Here’s a pic of “Wash” and his gravesite behind the church.

In 1864, Hopkins re-enlisted again bringing more men with him from Polk County as part of a 100-day unit of volunteers the Lincoln Administration had requested. And, again, more didn’t make it home. As the war crawled to its end in April of 1865, Josiah Hopkins would soon find himself, too, at the end of his beloved time on Iowa soil.

“It is apparent that Hopkins’ reputation within the community and standing within the church suffered irrevocable damage during the war years. The few remaining records available suggest that his zealous politics ultimately lead to his expulsion from the church and self-imposed exile to Kansas,” according to Higginbottom.

The Reverend Adams surmises of the situation, “Because of the active part he took in trying to put down the rebellion and save his country from destruction...some of his preacher brethren were jealous of him and tried to break him down and ruin him. Josiah had no peace for them, for they gave him no peace, until he sold out his beautiful home where he had fixed himself to live comfortably and where he was the main pillar in the church; and moved to Kansas where he was unfortunate in his investments and finally he took sick and died.”

The fallout from the war on this small, once tight-nit community was irreversible. Hopkins would sell all of his farm on May 9, 1865. The last mention of Hopkins officially being in Iowa is on July 22, 1865, in the 3rd Quarterly Conference of the Des Moines Circuit where he was listed among the absentees with the word “removed” next to his name. He would die in Kansas on July 16, 1867, and the whereabouts of his grave today are unknown. Some believe he was brought back to Iowa for final burial, but historians have been unable to locate a marker.

In my conversation with local historian Roxana Currie of the Big Creek Historical Museum seeking insights on the subject of Josiah Hopkins, she quipped, “regular people often get the shaft in history” and it’s stuck with me since the moment she said it. I think it’s one of the reasons I write songs like Up on Chorito Ridge that tell stories about regular people like my grandfather, PFC Richard D. Hixon that served honorably in World War II but first had to make it through the Dust Bowl. We broadly remember the big names like Lincoln and Grant when we think of the most defining conflict of the United States, but I can’t find a solitary picture of Reverend Josiah Hopkins on the Internet.

Yet it was the preachers and farmers and their families, in small communities like Hopkins Grove where many were religious pacificists, that tackled together a great moral dilemma of going to war or accepting the ongoing repugnancy of human slavery in their country. They were active participants in a historical outcome that created a greater good through the eradication of slavery. They endured unimaginable hardships as part of a heavy moral quagmire that resulted in the loss of their loved ones forever. They were a community swirling in alignment and disagreement through a tumultuous time.

Hopkins’ fervor and ferocity for the righteousness of the cause, supporting his young Nation in overcoming its most challenging moment since its birth, meant that the agrarian peace many sought would not be plausible at this time. There was a greater battle that first needed to be fought. Hopkins persuaded handfuls to join him, but the costs were of the ultimate consequence for many, including his own eventual eviction.

Despite their irrevocable differences in 1865, the church elders and community have always retained the name of Hopkins Grove and there are no records of any movement to create erasure of the Hopkins legacy on the area that I could find. They allowed history to have the chance to rediscover his legacy.

In 2026, Hopkins Grove will celebrate their 175th anniversary. This community has seen the darkest of times, but the light continues to shine through its gorgeous stained-glass windows upon its people. Their crisis point with the American Civil War passed long ago but they also tackled another crisis point with a discriminatory policy that had women entering through the back door for church services. They moved forward, rightfully changed course and now celebrate the actions of great women like Mary Albright Helms and Biddie Snyder that have made the congregation better over the years.

Even when general history is unable to properly recognize the role of the common person, it’s important that we find the time to do so because understanding the challenges and triumphs of those before us unlocks the mysteries of today. And good people have done great things just to get us where we are. It’s often said, “we stand on the shoulders of giants” that came before us, but I’m thinking the view from our backyard surrounded by empathetic stories of regular folks that endured great personal tragedy and triumph in the face of wrong will make us a better populace. I’ve found a simple exercise in empathy and local history is to pull over and walk through a graveyard or cemetery, stories and tragedies like the one below for the Wylie Family of Hopkins Grove provide me pause in these hectic times.

Since I was unable to locate a picture of Josiah Hopkins, here’s a picture of science-fiction writer Isaac Asimov to remind us in 2025 that “there are no happy endings in history, only crisis points that pass” as we regular people come together to make decisions about the future of this amazing place we call America and how we want ourselves to be remembered.

Special thanks to Steve and Mary Swalla Holmes, Reverend Dr. Craig Ferguson, Roxana Currie and Daniel K. Higginbottom for their previous works and conversations to make this history more accessible to others. If you are interested in learning more about this local history, Roxana Currie’s book Polk City Early History is available at the Fareway in Polk City. The Big Creek Historical Museum is also open on Thursdays from 5-7p. The Iowa Freedom Trail Project is a phenomenal resource for a more comprehensive understanding of the Underground Railroad in Iowa as well.

To find more stories and insights across the state of Iowa, please consider following and supporting the many talented journalists and storytellers of the Iowa Writer’s Collaborative of which I’m a proud member.

You can stream my original music on all platforms and learn more about me at www.chipalbrightmusic.com. My next show is in Williams Bay, Wisconsin, this Saturday, June 14th at 6pm in the new Green Grocer venue.

Also, here is the Zoom link for this month’s Office Lounge for paid subscribers to the Iowa Writers’ Collaborative. It’s a lively conversation held on the last Friday of the month at noon and hosted by Robert Leonard.